We’ve all been thinking about productivity in the wrong way. This buzzword that has made its way into office culture and university has been around for some time, but doesn’t quite hold the same weight or meaning anymore.

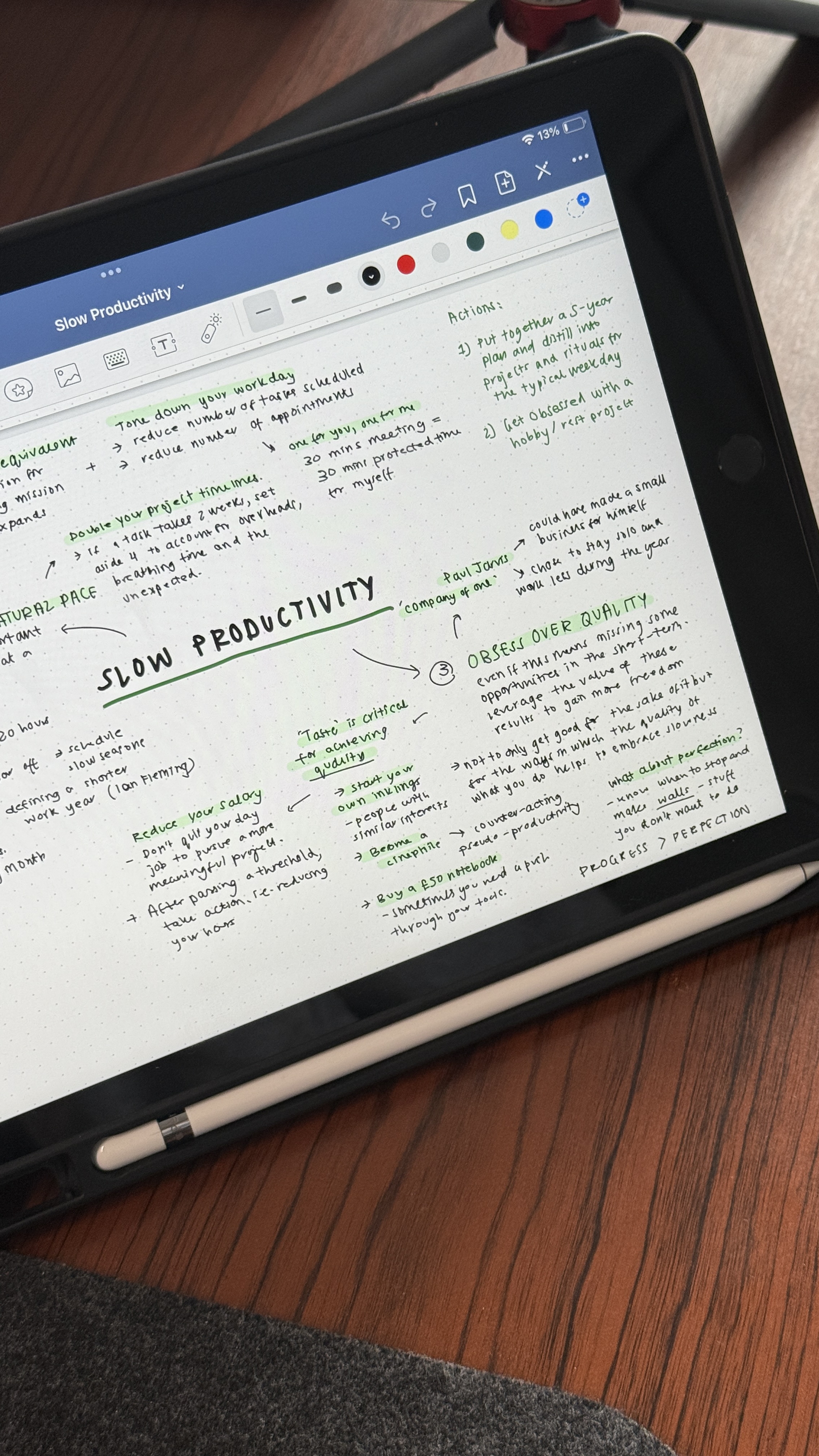

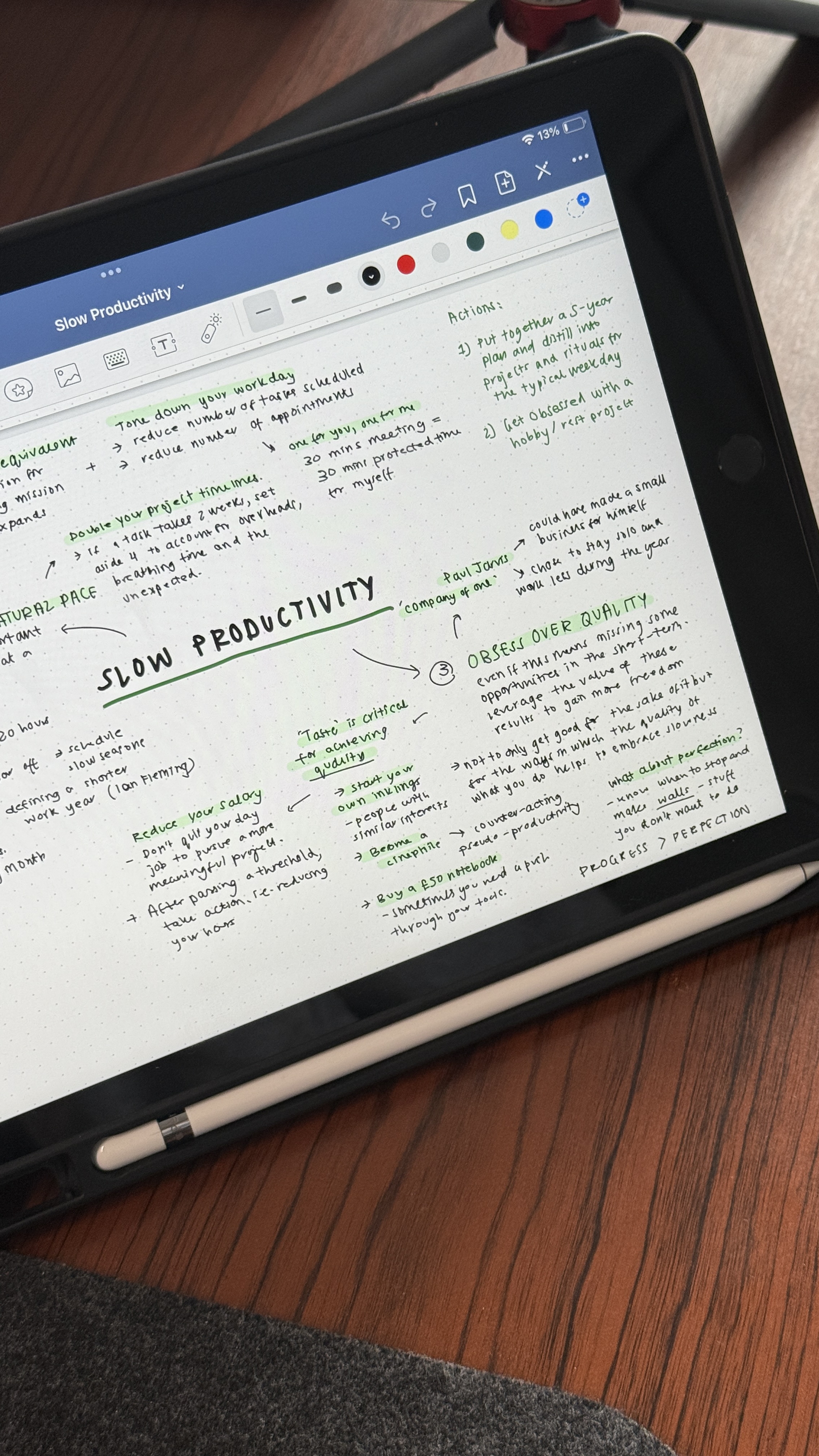

During the pandemic, the productivity space went through a major shift, being labelled as toxic and promoting hustle culture, leading to an anti-productivity movement. From there, the notion of Slow Productivity was revealed by author and professor Cal Newport.

At first, you might be thinking, how is a computer science professor teaching me about slow productivity at all related to being an architecture student? Productivity becomes a difficult and intangible metric when it comes to creative work, especially that of architecture.

We’re asked to produce an exceptionally high amount and quality, usually without a point of reference or structure. Architecture isn’t a degree with exams or a textbook to follow. So, how do you know if you’re truly being productive?

This concept treads the fine line of stereotypical working habits such as pulling all-nighters. In university, we think that the person working till 3 am surely must be producing work of a high quality or has more dedication to the craft. This is untrue.

As I learnt in Newport’s book, Slow Productivity, the first concept to grasp is called pseudo-productivity. This simply means the act of seeming busier than you are. All-nighters fall into this category, no doubt about it. There are some exceptions to this, of course, depending on how you break up your day and work according to your energy levels, but for the most part, most architecture students aren’t productive because they try to cram all kinds of work in the span of a few months.

This is also dissimilar to the way projects are run in practice. Many projects have long timescales, spanning years, and the design development is an ongoing, iterative process. You might not even be at the practice to see your project completed. The pressure to create, design and present a fully detailed building in just a few months pretty much outlines the flaws of the architectural education system.

At university, specifically during my Master’s, where I had more autonomy and control over my own work, I was able to avoid this typical way of working. A few things to note: I was taught by tutors who knew the best ways to push my craft without being overbearing or giving me the answers immediately. Second, there was a huge sense of independence, as is the case with most Master’s programmes in the UK. You’re in charge of your timetable outside of the 1 day you’re in the studio.

The first piece of the puzzle to slow productivity isn’t what you think it is. I blocked out time for myself before even thinking about university work. This meant that I had protected time during the week that was for me. Whether it was to explore the city, meet up with friends or just have a chilled evening, there wasn’t a day when I was working for more than 8 hours.

Some saw this as a high-performing trait that was liked by tutors and reflected in the quality of the work I was producing. Whilst others were scrambling to show more and more work each week, giving in to the pseudo-productivity construct, I was taking my time to reframe and iterate each week. This often meant that I only had two or three ‘pages’ of work to show, but there were many more big ideas churning away in the background.

There’s another complaint many architecture students have, which involves the overall workload and the associated time it takes to complete it. We often think that tutors love giving us more and more work in less time, whilst not appreciating the other modules or responsibilities we may have. What if these tasks are manageable from a slower perspective?

Alvin Zhu describes his cheat sheet tip for overcoming this myth in his video ‘how to survive architecture school (and actually enjoy it)’. Look at the marking criteria. This is something that you’re probably given at the beginning of the year, but ignore as just more paraphernalia. The marking criteria usually outline the exact deliverables for the project, and anything outside of this is extra. We end up focusing too much on the extra details, like having a colour-coordinated key to go along with the sun-path diagram and not enough on having clear drawings.

If the marking criteria aren’t available or don’t outline this, speak to your tutors to understand what the deliverables are, but also what components are going to help your project in particular. There may be certain aspects that are better explored through a physical model or perhaps through a series of sketches, but you don’t have to do it all.

I spent 3 months crafting my final piece, a model that I had designed and tested purely out of my own ideas. There was no reference or set of instructions, just ideas being pulled from work I had done or conversations I had had much earlier. To some, spending 3 months solely on a model might seem like a risk, but it encompasses the 3rd pillar of Slow Productivity, which is to obsess over quality.

There’s a tricky line that most creatives might struggle with. When do you stop working on something? What if it’s not perfect? The rule here is more straightforward to say and rather difficult to implement: progress beats perfection. As mentioned earlier, the timeline for a university project is already constrained, so there may not be a way at all to end up with a finished, perfect project.

Once you come to terms with this, it can help to separate the unnecessary work from the work that really moves the needle. Slow productivity isn’t just about spending longer on things, but letting them marinate or pushing things onto the slow burner rather than dropping the idea and moving on in a panic to churn out something.

Take, for example, large-scale hand drawings that you might have come across at university end-of-year exhibitions. These are the most impressive pieces of work, often getting commended or put up for external awards. For us, it may seem unachievable to create something with so much detail and depth because it simply takes too long. But the person who spent 120+ hours on the drawing has embraced the idea of slow productivity. It goes beyond just being a risk and actually ends up as a smarter choice.

I’d highly recommend reading Slow Productivity; it’s not a book that tells you the steps to be productive, but really just changes the way you see and define productivity for yourself. It’s also got a lot of eye-opening stories, looking to the past and applying similar principles to modern-day work.